Historically, Los Angeles, California’s Latino community has been left out of the planning dialogue on its Eastside neighborhood. Without a voice, quality of life in the community was set back by the removal of the street cars in the late 1950’s and the later construction of the numerous freeways causing displacement and air pollution. However, the Eastside Latino community has strong cultural resiliency that lives on despite all the social, economic, physical setbacks and lack of urban planning.

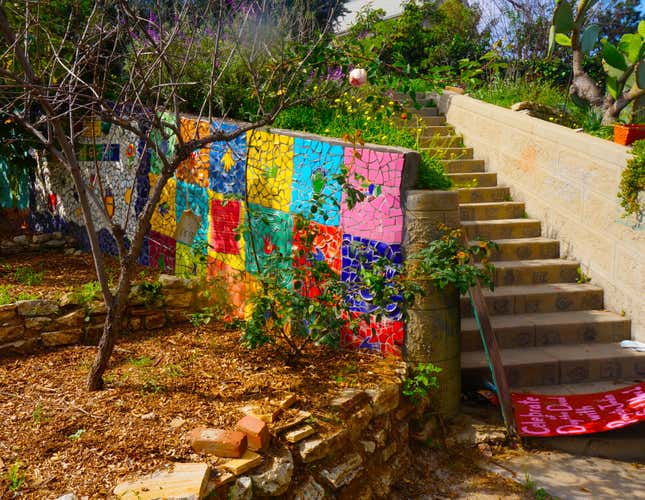

East Los Angeles is rich in the production of art. Since the Civil Rights movement in the early 1970’s, Chicano artists and area residents have used the physical form of their community as a canvas for self-expression. The verve of the Latino community in East Los Angeles will always live on through the music, narratives, and the visual arts created by its artists.

Despite these cultural, social, and visual interventions, urban planners often ignore these cultural assets, which are rarely found in the local planning and zoning codes. Unlike most US communities, which are created and regulated by zoning codes, there is no Latino urbanism zoning code. The Boyle Heights’ zoning code is similar to the West Los Angeles community of Mar Vista, but these communities feel, look, function very differently. The planning documents do not reflect the community in the visceral way art does.

Chicano artists, specifically, can help preserve and enhance the Latino community’s values through the urban planning process because they offer new methods of planning inquiry and engaging with residents. Many Chicano artists have a good grasp of the Latino built-environment because many were raised in this community, which inspires their practices.

As part of my MIT thesis, “The Enacted Environment: The Creation of Place by Mexicans and Mexican Americans in East Los Angeles,” I investigated my community’s identity of place, through the lens of sociology, anthropology, architecture and urban planning.

Through their cultural, social, and economic behavior patterns and needs, Latinos imagine, investigate, and transform their physical landscape. For example: a fence becomes a place of social interaction; a store sign becomes a work of art; and a front yard becomes a plaza.

Planners often lack the tools to investigate and understand this built-environment, or take seriously these interventions, even though they are creating such a palpable sense of place and neighborhood identity.

It was not until I opened up Gallery 727 on Spring Street in Downtown Los Angeles with Adrian Rivas that I realized what urban planners could learn from artists like Sandra de la Loza, Gronk, Arturo Romo, Mario Ybarra Jr., Karla Diaz, Raul Baltazar, Carmen Argote, York Chang, Elana Mann, and a host of others. Through the gallery, I explored the intersection of art and urban planning through collaborating and learning from these artists and curators.

For us, the building blocks of a city comprised more than simply structures, streets, and sidewalks but equally encompassed personal experience, collective memory and narratives. We felt these were the less-tangible, but no-less-integral, elements of a city that transform mere infrastructure into place. We generated exhibitions and dialogues on artistic representations and interpretations of the urban landscape, which were expressed through photography, painting, writing and video installations. While these artists saw their work as expression and representation, I saw the work as reframing urban planning.

Urban planners and artists occupy the same city space. Yet, artists take a different approach to exploring, understanding, and presenting urban issues. Urban planners begin their inquiry of place by collecting data in the form of numbers, maps, policy, and maybe a site visit or talking to people. Artists, on the other hand, begin their inquiry by using their body and senses to explore the site and ask a series of questions such as:

How does the site feel?

What do I see or not see?

What are the urban patterns playing out within the site?

What are the relics here?

The site determines the outcome of the artist’s work. When the artist’s work becomes site specific, it has the power to engage, educate, and empower the public on urban issues. The urban plan, on the other hand, often is a generic document that will most likely sit on a shelf.

Artists put themselves out there in the public’s eye because they are not afraid of the public. Urban planners sometimes dread dealing with the public and times they hire consultants to do their public engagement.

Artists communicate with residents through their work by using the rich color, shapes, behavior patterns, and collective memories of the landscape than planners. Urban planners use abstract tools like maps, numbers, and words, which people often don’t understand.

Like artists, curators also spend time developing and designing the best way to arrange an exhibition in order to maximize the public’s interaction and inquiry with the art. For curators like Pilar Tompkins Rivas, Chon Noriega, Rita Gonzalez, and Bill Kelly Jr., how the art is presented is just as important how it is produced. Urban planners, on the other hand, use online surveys, stick maps on walls, and present Power Points that don’t engage the public. The public meeting, survey, and their planning tools rarely transforms or inspires the public in the way an art can.

Art venues are designed to engage, transform, and inspire the public by their nature. Public meetings, on the other hand, are frequently scheduled at awkward times, poorly attended, have a rigid agenda, and do not promote creativity. Public meetings are can oftentimes become combative between differing interests. People generally leave an art venue satisfied, wanting more, while people leave a public meeting thinking, “Thank God it’s over.”

Through my involvement with Gallery 727’s cadre of artists and curators, I was able to experiment in applying art to urban planning. I learned that urban planning is an art practice because people imagine, investigate, and construct their environments the same way an artists creates their work.

As planners we should embrace the public creativity and not squash it. Through artistic practice, we can directly involve and engage participants—as opposed to “audiences” or passive viewers—in a creative and collaborative city planning process to bring people together to imagine and actively design better communities. This method will help us enhance, preserve and develop the Eastside in equable ways.

I recognize the beauty in a piece of art, but have learned the most important part of the art is the process that created it. Like urban planning it’s the process of how we create our cities that I am draw to. My newly found interactive urban planning process, or Place It, applies the creative process to urban planning. My method helps people investigate how their memory, experience, and imagination shape their environment and how we as planners can capture this information to inform public projects, plans and policies.

This approach I started at the gallery is revolutionizing the way people, especially youth, immigrants, and women imagine, investigate, negotiate, construct and reflect on their communities. I have facilitated over four hundred of these interactive workshops and built hundred’s of city models, engaging thousands of participants all over the US, Mexico and Canada. However you will rarely find my practice in galleries or exhibition but rather in the laundromat’s of the South Bronx, the shopping malls of Calgary, the classrooms of East Los Angeles, or on a city’s streets, sidewalks, and open spaces.

Above all, I am committed to the idea that people’s imagination and creativity—based in their on-the-ground knowledge about what does and does not “work” in their communities—can shape their future. This is how Latinos shape their communities.

Many Chicano artists are passionate about the Latino landscapes that inspire their work and spend a whole career reflecting on it. While most urban planners take an indifference toward the communities they serve and jump around from city to city.

The City of Los Angeles should apply to an Art Place much like Minneapolis did, to embedded artists in the Los Angeles Urban Planning Department. Or the city should contact the James Irvine Foundation, California Community Foundation or many others that are interested in improving the quality of life in Latino Communities. Chicano artist’s can be that instrument to transform urban planning from an exercise to an experience. It can raise the Latino consciousness of the built environment around them and how it impacts their daily experience of place.